Once California was a formless void, a land of milk and honey punctuated only by orange groves. Then the heavens parted and the automobiles and buildings came. Some buildings were shaped like giant donuts. Some were shaped like puppies and, appropriately enough, dispensed hot dogs. Some were shaped like hats and dispensed foods that didn’t resemble hats at all.

Once California was a formless void, a land of milk and honey punctuated only by orange groves. Then the heavens parted and the automobiles and buildings came. Some buildings were shaped like giant donuts. Some were shaped like puppies and, appropriately enough, dispensed hot dogs. Some were shaped like hats and dispensed foods that didn’t resemble hats at all.

Much of this fantasy land is gone or in ruins today, but thanks to Jim Heimann’s painstaking research, we armchair archaeologists can explore long-forgotten offbeat buildings through words and photos. Against a colorful backdrop of giant stucco bulldogs and pumpkins, he weaves a mesmerizing tale of how land speculators, nascent suburban sprawl, and the rise of the automobile led to a unique architectural form, the figurative building.

It’s hard to remember now after decades of smog, riots and sprawl, but Los Angeles was once a promised land. With abundant jobs, good weather and lots of space to grow, it lured countless Steinbeckian Joads down the Mother Road away from the dust bowl or their own particular places of darkness and cold.

With them, immigrants brought diverse architectural traditions and a willingness to experiment. It was an adventurous time and place, an era of world’s fairs and expositions and a fascination with the exotic. As a result, Southern California architecture became unrestrained, with builders indulging in an exaggerated pastiche of elements borrowed from cultures around the world.

“While many of these types of architectural styles … were not exclusive to California, their confluence and impact on an emerging landscape was a striking contrast to companion structures … in the other parts of the United States. It was becoming clear that California was slowly becoming crazier,” Heimann notes.

Hollywood made its contribution as well, with fantasy buildings literally oozing out the studio gates into town. In some cases, set builders were commissioned to design homes or stores, as with Van de Kamp’s Bakery outlets. Designed by Harry Oliver, an art director for Fox and Metro studios, the outlets featured a series of small-scale Dutch windmills with exaggerated styling.

Hollywood made its contribution as well, with fantasy buildings literally oozing out the studio gates into town. In some cases, set builders were commissioned to design homes or stores, as with Van de Kamp’s Bakery outlets. Designed by Harry Oliver, an art director for Fox and Metro studios, the outlets featured a series of small-scale Dutch windmills with exaggerated styling.

Heimann quotes a 1928 visitor to Los Angeles:

“If this manufacturer had traveled through California without pre-warning and without stopping to investigate, he might have come away with the idea that the movie people had been so rash as to invade even the residential districts of the cities there in establishing ‘locations’. What else could a tourist think who, knowing by hearsay something of the prevalence of studios and the studio folk in that state, found himself whirling past gigantic ice cream freezers, snow block Eskimo igloos glowing in an electric aurora borealis by night, mammoth ice cream cones, and sparkling ice caverns, all established on the city streets or at vantage points along the open highway?”

While architecture in most of the world is constrained by the need for protection from the elements, that wasn’t the case in Southern California or much of the American desert southwest. One could have a building shaped like a donut without concern for its roof falling in under the weight of snow or being ripped off by a tornado.

Into this heady brew of affordable real estate, congenial weather, and freewheeling residents came the automobile. Suddenly it was not only possible to have a building shaped like a donut, but an eye-catching business advantage. Just as preliterate mankind depended on pictorial signage in the shape of a coffin or boot or anvil, drivers whizzing by a lemonade stand were greatly aided when that stand was shaped like a lemon:

“Throughout California, the main roads leading into metropolitan areas were the obvious place for refreshment stands, eateries, and other businesses to solicit the auto trade with unusual imagery. Enticing motorists who were driving by at thirty-five miles per hour required eye-catching and flashy solutions,” Heimann writes.

“Throughout California, the main roads leading into metropolitan areas were the obvious place for refreshment stands, eateries, and other businesses to solicit the auto trade with unusual imagery. Enticing motorists who were driving by at thirty-five miles per hour required eye-catching and flashy solutions,” Heimann writes.

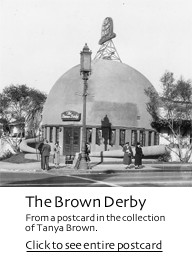

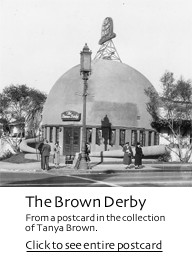

It was the figurative made literal, a movement whose golden age lasted for about ten years, from 1924 through 1934. This period would see the building of such improbable structures as the Hoot Hoot I Scream stand, the Hollywood Flower Pot and of course, the Brown Derby

Surprisingly, the Great Depression “rarely deterred the construction of programmatic buildings,” Heimann notes. “The inexpensive nature of a modest building and the still-affordable land made many of these investments worthwhile.” But by the middle of the 1930s, oddball buildings began to fall out of favor. New styles like the Streamline Moderne were embraced as progressive and new. Only a few structures, most notably those emulating sailing vessels, were able to successfully blend the old and the new.

World War II brought rationing of building materials and gasoline, which severely restricted travel and new construction. “It was in this critical period of disfavor that some of the best programmatic buildings disappeared. Never intended for long-term use, the buildings’ fragile nature made them vulnerable to adverse conditions, and a crowded wartime L.A. made demands on every parcel of premium land,” Heimann observes

But the war also yielded new technologies that would be used in roadside signage and statues in the 50s and beyond. Giant fiberglass fruits, beasts, and leering men bearing mufflers began to grace roadsides where the stucco hotdog stands had once stood.

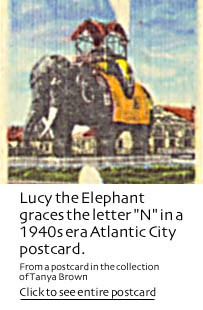

While Southern California was the nexus of the figurative architecture movement, it was by no means isolated. Today you can still find a few lonely examples of figurative architecture scattered around the country. However, most of Southern California’s eccentric buildings are only a distant memory, supplanted by the prepackaged fantasies of Disneyland and Las Vegas.

Heimann’s book catalogs these treasures, both lost and extant, with copious photos selected with a designer’s eye for detail and a historian’s keen perspective. For anyone who’s ever wondered about the birth of roadside architecture, this book is an indispensable resource.

Get book from Amazon.com